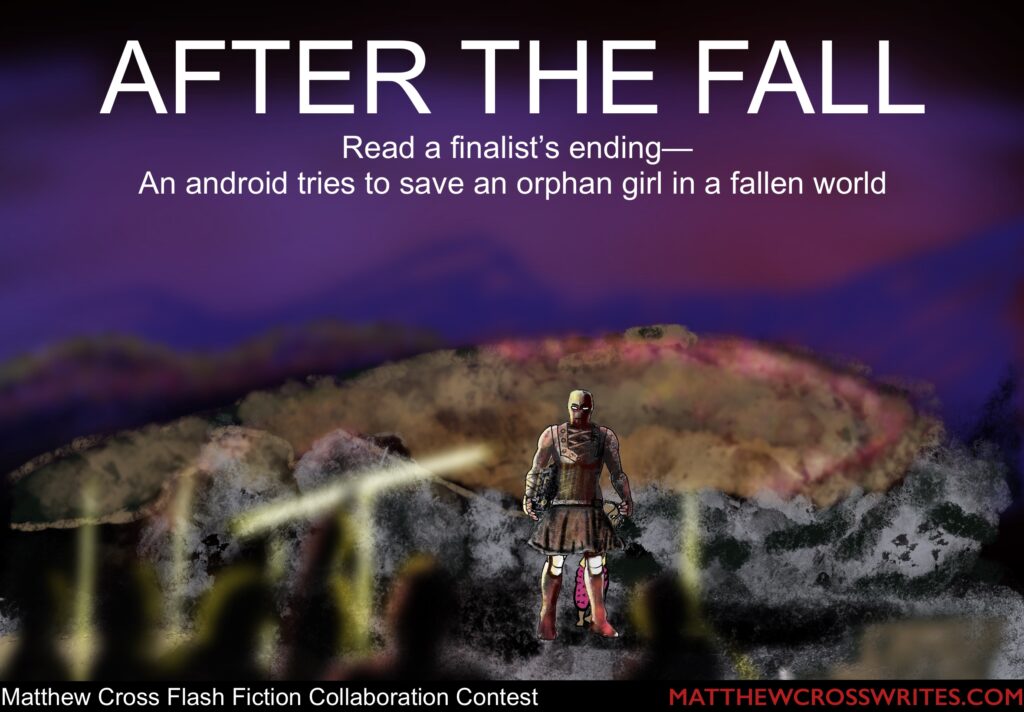

I’m sharing finalist stories from the September Contest. We have 3 finalists, and here is the last finalist story, a prize-winning ending by Alan R. Paine. Enjoy Alan’s fun, fast-paced, and upbeat ending!

After the Fall

BY ALAN R. PAINE AND MATTHEW CROSS

Something is wrong with me.

Seriously wrong.

I am an android, and I am thinking in the first person. That’s not right.

Or is it?

I trudge through the late afternoon wreckage of Stockheim, the largest city near Dr. Herbst’s country villa. After the Pulse, only a few humans remain in Stockheim.

Everything is broken, including me.

I’m forgetting things.

That’s not right, either. I don’t forget things. I store data; I delete data. But ever since Dr. Herbst started filling my files with his library, I’ve had trouble accessing operational files. Dr. Herbst used every bit of available space in my networks to save the planet’s culture and history. He should not have done this. He said so himself.

“I should not be doing this,” he said. “If you were a human, this would fry your brain. That’s a technical term, of course.”

He chuckled to himself.

I have not been programmed to laugh. It’s not a necessary feature for a housekeeper android.

The record of that conversation with Dr. Herbst is a waste of storage space, but I no longer control what observational records I keep in long-term and short-term storage.

That’s not right.

Sometimes, usually at night under an open sky, I can access data from one week prior and set it for auto delete after 98 hours. I don’t know why that is the best time or why 98 hours is the most likely setting to work. But most of the time, I cannot delete the records stored throughout my frame that struggle for energy and resources.

Bits and pieces fly through my Opsys, causing a variety of tics and malfunctions.

So I will probably have the memory of that conversation until I can find another repository to download the massive library Dr. Herbst loaded into me.

I stop next to a moldy couch that has been singed on one corner. I tilt my head. I can hear the aria “How I Wept After the Fall,” sung by the virtuoso ultima soprano M. Cadere A. Gratia, from the operetta The Fall of Rome and Other Ancient Myths. I do not control what recordings play through my current observational mode. I do not think they are random, but I cannot detect a pattern.

The aria will last 6.29 mins. I stride swiftly but carefully down the four-lane road littered with mattresses, burnt-out hovers and even some human and animal bones. Most of the windows in the row houses are empty or just lined with jagged little teeth of glaze. Some few have been boarded up since the Pulse. Those houses may be occupied by any number of factions that compete over this wasteland.

“Be careful,” Dr. Herbst had said. “The Nature Cons Faction may still have a few EMPs left.” He stopped, breathed heavily and wiped his brow. “If they knew what you carry inside you–all our culture; all of it–I’m sure they’d let you pass. But they won’t stop to listen. As soon as they see an android, they’ll trigger an EMP if they have one.”

Dr. Herbst said some people believed the Nature Cons created the Pulse. Some believed it came from the sun. Still others believed it came from some unknown enemy in space.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” Dr. Herbst had said, breathing heavily. “It’s been years since the Pulse and there’s been no invading force. No, I don’t think it’s the Polity or the Republic. I think we did this to ourselves, and no one is coming to save us.”

Based on his respiration, pulse and the pallor of his face, my emergency protocols tried to call a first responder unit. But there are no more first responder units anymore, just the factions. The Nature Cons, the Savages, the Retro Cons, the Delirandos, the White Balance and others even Dr. Herbst did not know. After the first time I called an emergency response unit, Dr. Herbst’s scanning gear picked up the signal and he removed my transmitters. Now I can scan for signals, but I cannot transmit.

“That’s for the best,” Dr. Herbst had said. “All the factions scan for signals. No point in making it even easier for them to track you.”

My scanners are useful. I can often use them to avoid the roving bands of humans. I also used them to find the trace signals emanating from an operational hover buried beneath a collapsed bungalow. The hover got me from Dr. Herbst’s villa into the outskirts of Stockheim before it tilted 90 degrees on its side and began to smoke. I scrambled awkwardly from the seat, fell to the ground and limped away to get as far as possible from the pillar of rising smoke that would draw attention.

My legs are operating at 95 percent of optimal performance, which is one reason Dr. Herbst retrieved me from the basement of the Acosta’s house. That’s where I plugged myself in after the Delirandos killed the Acostas. My preservation protocols directed me to place myself between the Randos and the Acostas, but the Randos surrounded me and then pinned my right arm to the wall with a sharpened metal post. They made M. Acosta cry a lot before killing both of the Acostas. I recorded the event for law enforcement.

“There is no more law enforcement,” Dr. Herbst had said. “No point in keeping that horrible record.”

He used that data space to store part of the Music Collection. Sometimes when I detect danger, my Opsys pulls music from that file.

I have scoured Stockheim for a storage device large enough to hold even one segment of Dr. Herbst’s library. All I’ve found so far is a bulky black data box that’s even older than I am. I’ve lashed it under my right arm.

The aria ends, but I still hear a high-pitched, warbling tone. It is only detectable via sound waves, so the source is not electrical. Images flash through my Opsys. An instructional video on carpentry featuring a whining saw. A siren from an entertainment drama labeled “law enforcement procedural.” A sound clip of a crying baby.

I think it’s the sound of crying. Not a baby, but a child. The Acostas did not have children, so I do not have the nanny software bundle, but I do have a basic childcare protocol intended for short-term use. Dr. Herbst stuffed the file with images from the Central Museum of Art: oil paintings, plastic paintings and dynamic light images. The pieces of childcare information I can access indicate a child–likely a female child between the ages of 4 and 5–is crying from fear but not a recent physical injury.

I cock my head and set my audio receivers to maximum sensitivity. I do not know why I cock my head.

The sound of a crying child could be a trap, of course. But my childcare protocols send an insistent signal and the images of two abstract paintings to the Fundamental Rules programing in the Opsys. The Opsys filters out the two paintings–one of a screaming man and one of a child ballerina–as irrelevant.

I spend 33.79 mins locating the child. I walk through the wide open doorway and find her standing in the middle of an explosion of ancient splinters and wet carpet remnants. The damage to the room is old. It’s not a good setting for a child, but it is not the cause of the child’s trauma. She is wearing pajama bottoms and a halter top showing a yawning cartoon lion on the front. Both are filthy. The childcare protocols make a Level 5 recommendation to remove the soiled clothing and replace it with appropriate attire for a temperate Autumn afternoon. A quick visual scan of the room shows no alternative clothing is available.

Her face is smudged and mucus drips from her nose, but she shows no apparent injuries. The gauntness of her face shows she has been undernourished for some time, but without medical or nanny bundles, I cannot estimate how long. Even so, her stomach bulges underneath her shirt with baby fat, so the childcare protocols make a Level 3 recommendation to locate food within the next 4 hours.

“Are you injured?”

The child stops crying and stares at me with large, liquid eyes. She whispers something unintelligible.

“Are you hurt? Do you have a boo-boo?”

She silently shakes her head.

“Where are your parents? Where is Mommy?”

“Kilt,” says the girl.

I quickly check my files but cannot find any relevance of a men’s clothing item.

“Point to Mommy.”

Following the child’s pointing finger, I find the body of a woman in a half bathroom with melting laminate walls. I check for signs of life and then record the obvious murder details visually. The Opsys allows me to set the record for automatic deletion after 50 years.

I return to the child. “Where is Daddy?”

“Daddy leff us,” the girl says. “He don’t . . . “ She pauses and mumbles to herself. “We onner own, baby girl.”

Androids are programmed to be ambidextrous, but Dr. Herbst recorded over all but the most basic functions for my right arm and hand, since the arm was damaged. It mostly works, but my right-hand grip only operates at 50 percent capacity. That’s why I had to lash the data box under my arm.

I offer my left hand to the girl. Holding her hand will significantly lower my defensive capability. But I have no weapons and I am only programmed with rudimentary defense-of-android and defense-of-humans routines.

“Come with me,” I say, pitching my voice to imitate a middle-aged, female woman.

The child wipes her nose absentmindedly with the back of her hand and then takes my left hand.

It’s time to leave Stockheim, anyway.

Perhaps a larger city will have what I’m seeking.

As we walk through the suburbs, I scan the surrounding buildings that likely would contain food. All the stores would have been scavenged years ago. I am programmed to make thousands of dishes based on processed and fresh foods. But I am not programmed to hunt or butcher food. A quick probability calculation shows that taking the child with me will lower the efficiency of my search for data storage by 43 percent. It will also increase the chances of being detected by a roaming faction by 57 percent and decrease my defensive capabilities by 69 percent.

I hear dogs baying 1.2 kloms away. The number of dogs and their spread pattern indicates a high likelihood they are being directed by humans. I pick up the child and we flee.

Even carrying the data box and the child, I can walk faster than most humans can run. For 18 mins, we place distance between ourselves and the hunters. My Opsys estimates a high likelihood they have not detected us and are not pursuing us.

At dusk, we find the crater.

The large suburban neighborhood abruptly stops at the edge of a cliff leading down to the crater floor.

I cannot tell whether the crater was created by an object that fell from space, a terrestrial missile, or a placed explosive. It measures 0.48 kloms across.

A footpath has been carved by years of foot traffic down the inside of the steep wall of the crater. I scan the shadowy crater bottom and estimate the time to cross the crater. As I turn my head to scan a path around the crater and compare the alternative paths, I hear the first sintar strums of “Come Dance with Me, Danger” by the Plundered Sphinxes. Thrum, thrum, thrum-thrum-thrum.

I tilt my head and see the first lightsticks on each side of us. I swing the child to the ground and turn to face the way we came. Humans carrying long, glowing poles appear on the street we came down. Others stream from nearby houses. We are surrounded with the crater to our backs.

I scan the humans for respiration, pulse and facial expression. The childcare program sends a Level 10 recommendation to my Opsys: Do not allow the humans to take the child. Dr. Herbst’s custom programming sends a countermanding directive to preserve his library contained within me. All the culture left of this fallen world.

I gently push the girl and point down the path. I do not know her name. “Run, baby girl.”

There is a hubbub of voices from the gathering crowd.

“Hey, that’s an android.”

“How did it survive the Pulse?”

“Underground maybe.”

“Could be dangerous.”

“I am carrying a library of music, literature, science, art, films and television,” I say. “All that remains of our culture.”

“Not your culture. You’re a freaking android.”

A large stone arcs through the air, striking me in the body.

I am confused. Don’t these people want to preserve their precious culture like Dr. Herbst said they would?

A person carrying a cylinder over their shoulder steps forward. My weapon recognition program is slow to act, swimming through the load of data that I am carrying. Then, almost too late, I know it’s a EMP grenade launcher. The grenade flying towards me only has to stick to my body, emit its deadly pulse and it’s goodnight to everything. With my good arm, I pick up a piece of wood lying near my feet, whack the grenade back to where it came from and dive down the near vertical side of the crater.

The girl screams as I scoop her from the path and carry her–half running, half falling–into the shadows at the bottom of the bowl. Voices behind us fade. We are safe for now.

I run my diagnostics. The high-speed emergency action has affected the music library, deleting a block of Baroque Concerti Grossi, whatever they are, or rather, were.

“You OK?” I ask the girl.

She nods, but my childcare protocols show she is weak.

The sun rises ahead of us. The city is far behind. After climbing up the other side of the crater, we had passed through a forest where the girl had drunk some water from a fast-running stream. She had jumped down from me and consumed a large quantity while I was still analyzing the risk.

Now, she is sleeping in my arms as some buildings come into view ahead of us. Friends or foes? Culture lovers or not?

People are all around us. A woman takes the girl from me and offers her a piece of bread.

“What faction are you?” I ask.

“All the factions ’round here wiped each other out. We are just people trying to survive.”

I explain about the data that I am carrying and the importance placed on it by Dr. Herbst.

“But what use is it if it’s inside you? We can’t see or read it,” says a girl of about thirteen.“

“It can be printed or transferred to other data management devices like this box I am carrying,” I say.

“Do you have the special cable required to load the box?” the girl asks.

“No,” I say

“We have nothing like that,” says the girl. “You will have to tell us the information so that we can write it down.”

“My operational life will only be enough to pass on a tiny fraction.”

“Well, there’s no time to lose,” says the girl. “Let’s get to work.”

I hope you enjoyed this piece of flash fiction that Alan R. Paine and I wrote together. He’s a great collaboration partner!

If you enjoyed Alan’s prize-winning ending, please make sure and share some kind comments below.

Be stellar!

Matthew Cross

Great work Alan. Sounds like they have a whole lot of writing to do.